This website uses cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.

Josiah Jones ’25

I joined the Immigration Law and Advocacy Clinic (ILAC) after spending my 2L year working in the Farmworker Legal Assistance Clinic with Professor Beth Lyon. As part of the Farmworker Clinic’s brief advice and referral project, my clinic partner and I conducted an intake on a case that we were able to refer to Professor Jaclyn Kelley-Widmer and the ILAC. Once in that clinic, I realized that my knowledge of immigration law only scratched the surface of the greater issues prevalent in U.S. immigration. I wanted to learn more about the asylum process, both to be competent counsel for my client and for my own knowledge. I also wanted to take the ILAC to learn more about the realities of life and the legal processes open to undocumented persons in the U.S.

This fall, we took two trips to immigration detention centers — one to the Buffalo Federal Detention Facility in Batavia, New York, and the second to the Southeast Louisiana Detention Facility in Basile, Louisiana. During these two trips, I met directly with detained people seeking asylum or other permanent status in the U.S. The Batavia facility houses men, and the Basile facility houses women. Both hold immigrants from all around the world, including Georgia, Senegal, Korea, China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Venezuela, and Mexico, among other countries.

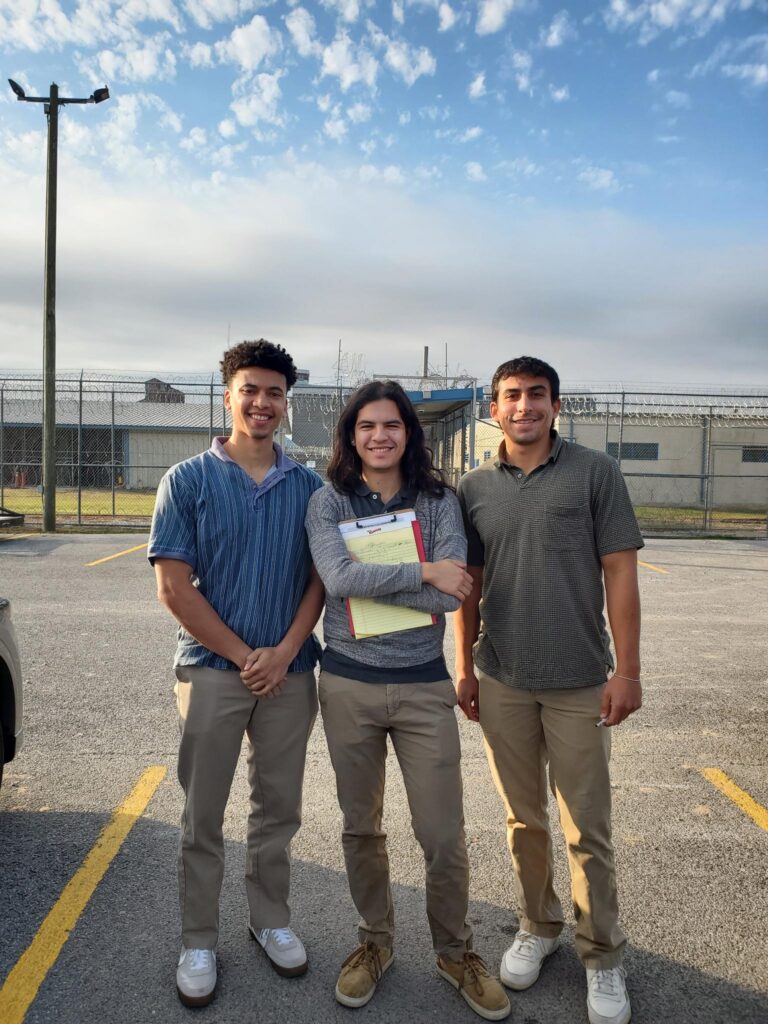

Jones, John D. Camacho Orona ’25, and Rodrigo Tojo Garcia ’25 outside the detention center in Basile, Louisiana.

In Basile, our team of two attorneys from RFK Human Rights and ACLU of Louisiana and three students met with more than 150 detained women in two days. Every woman I spoke with left their country out of fear, either from government forces, political violence, or persecution. Undoubtedly, every person detained in the facility has undergone more severe and traumatic experiences than many of us ever will. And, for these women who have undergone so much, they now feel hopelessness in a new form because of our country’s desire to jail them and refuse their legal claims.

For these detained women, they face a system that is designed to make them fail. Beyond the sheer complexity of the system — which is challenging even for lawyers to navigate — there is added difficulty because the court requires all submissions to be in English, even for pro se respondents. In my meetings, I had to quickly explain, through phone interpreters, the convoluted immigration system to individuals who faced anxiety and uncertainty in their attempts to remain in the country.

The largest complaint across both facilities was the lack of access to information in their native languages. We spent considerable time simply explaining court documents to detained people via telephone interpreters so they could understand what is being asked of them in their cases. Meetings often occurred in a loud, echoing room with forty other people waiting their turn. In one session, I spoke to twelve Chinese women who spoke Mandarin. Because the room was too noisy to hear the phone interpreter, we went out to the hallway of the solitary confinement wing. There, I attempted to answer questions and advise women in every stage of the immigration process. Some women had just arrived, while others were years into their cases. All of them desperately wanted their questions answered. One woman told me she was old, weak, and uneducated. She gestured to her papers and asked why she had been denied asylum. As I looked at the papers, I quickly realized that they were not asylum papers at all, but rather a denial of parole. As I explained the difference, I realized just how little this woman understood about her case. It saddened me to realize that countless people enter this country and are turned away for reasons they do not even understand. In other areas of law, we call this injustice, but in immigration, it is the norm.

During these conversations, I realized that complaints went much deeper than mere administrative annoyances. Many detained people reported cold conditions in cells and lack of adequate clothing. The temperature difference between the inside of the facility and the Louisiana temperatures outside would regularly be more than thirty degrees, exacerbating sicknesses, which were prevalent in the facility. We could not meet with women from several of the dorms because there was an outbreak of tuberculosis. Because of the heat outside, the detention center officers claimed they had no duty to supply detained people with additional clothing. So, these women in orange jumpsuits would shiver as they stared at the officers walking around in winter coats.

In the same facility, in another unit with more than ten women sharing a single towel, one woman told me she finds the guards, the jumpsuits, and the ten-foot-tall barbed wire fence comforting. “For me, I know the moment I set foot on the ground in my home country, I will die,” she said. This more optimistic young woman is relieved to be free from the danger of her home country, even if that means being in custody. Yet despite witnessing atrocities and being personally victim to them in her country, she remains in detention with no end in sight, as her court dates are continually pushed back.

After experiencing dozens of interviews during my days in the centers, I returned to my Ithaca-area asylum case with humility and increased energy. My experiences in the detention centers took me out of the comfortable and purely observational world of academia and into what my life could have looked like had I not had the privilege of being born in this country. Moving forward, as I continue to advocate for my asylum clients together with a team of other law students, an interpreter, and our professor, I am confident that I will be able to make a true difference in my clients’ lives.

These experiences have demonstrated to me the importance of being both prepared and willing to step up and take on more after committing to assist someone in need.