This website uses cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.

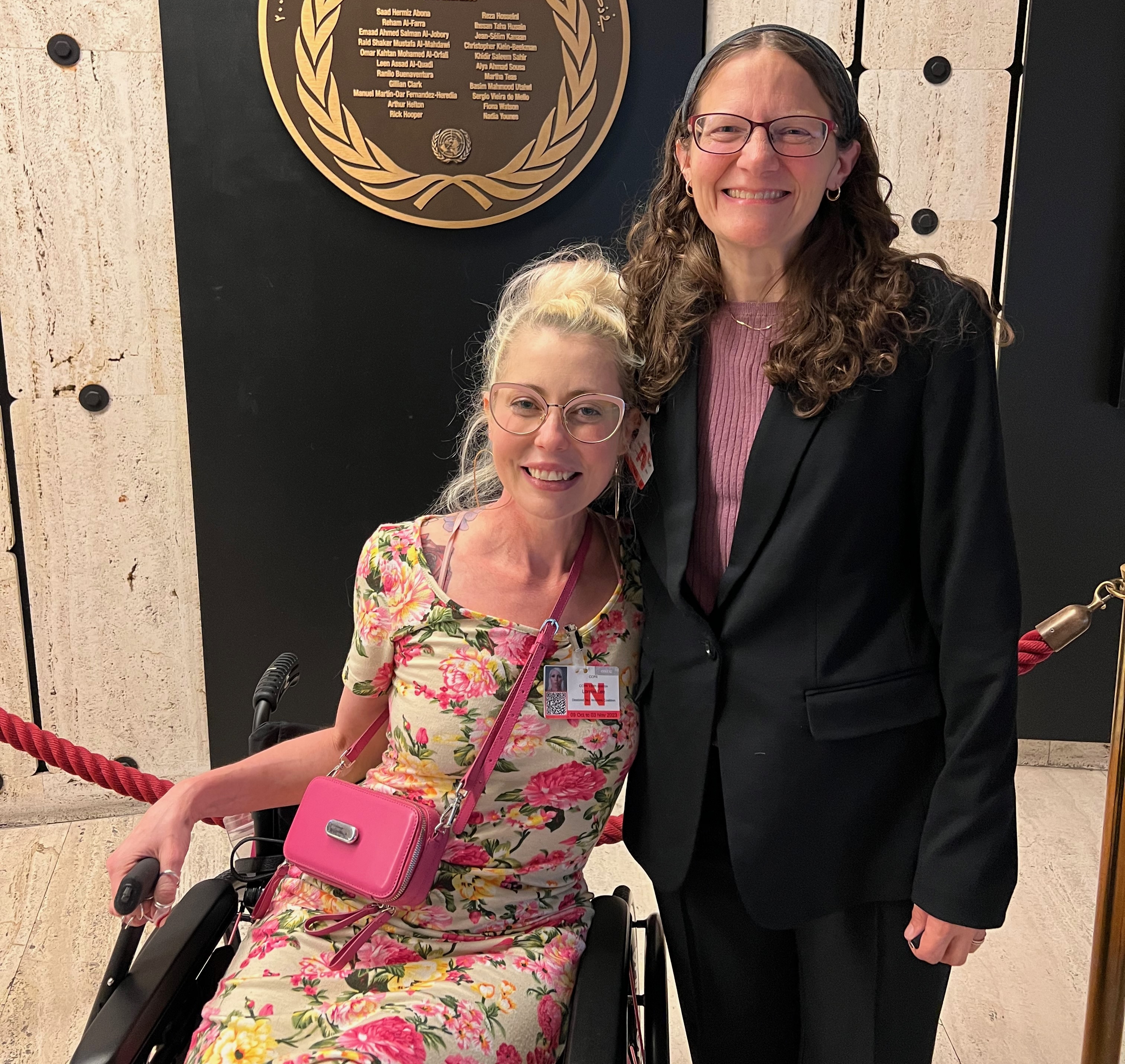

Nearly a decade after launching targeted advocacy for victims of military sexual assault, faculty, students, and alumni in the Gender Justice Clinic recently traveled to Geneva, Switzerland, to present recommendations on this and sex workers’ rights in hearings before the U.N. Human Rights Committee.

The Cornell team joined more than 140 U.S. NGO representatives, experts, and individuals working on and directly impacted by a wide range of human rights issues.

As a member state of the United Nations, the United States agrees to abide by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, a part of the International Bill of Human Rights. Member countries participate in periodic reviews of their human rights records before the committee, which seeks not only an official government accounting but also submissions from contributors representing civil society. The committee then issues observations and recommendations.

“It’s important for civil society to hold the United States accountable for actually living up to its human rights obligations. This is a part of a broader process of both international and domestic advocacy,” said Elizabeth Brundige, clinical professor of law who coteaches the clinic.

The Gender Justice Clinic began the work in 2014 with regional human rights lawsuits filed in the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Clients had been sexually assaulted in the U.S. military and had suffered retaliation for speaking up, through denial of benefits and other rights.

The cases were ruled admissible in 2022. In the meantime, the clinic has kept a spotlight on these issues and others by taking them to the international stage.

Clinic team members submitted two shadow reports to the U.N. committee in September, in advance of its periodic review of the United States.

One report focused on sexual assault on members of the military, particularly violence against women and LGBTQ+ service members. It addressed the gaps in prevention, response, and redress for victims and survivors.

“There are very critical gaps throughout the system that need to be fixed,” said Pilar Gonzalez-Navarrine ’24, who spoke in Geneva about the experiences of LGBTQ+ service members. She told the committee that transgender individuals are particularly vulnerable to discrimination.

In their observations released last week, committee members didn’t directly address transgender rights in the military, but they did echo support for many of the changes the LGBTQ+ working group was seeking: better services for victims and more robust legal remedies, including training for lawyers and judges within the military system and access to the civil remedies that are available to civilian survivors.

The next step will be to leverage the committee’s observations for domestic advocacy with partner organizations in the lobbying space, Gonzalez-Navarrine said.

The clinic’s second shadow report focused on ending human trafficking. The U.S. approach to prevention has been to criminalize sex work, Brundige said. But experts and industry workers from the clinic explained that the opposite is needed: Decriminalizing helps prevent trafficking by removing barriers to social safety in income, housing, food, transportation, and other essentials for survival.

For both reports, the Cornell team included people directly affected by the issues who read statements and engaged with the committee.

Lorelei Lee ’20, who coteaches the clinic with Brundige, led the effort on human trafficking and sex workers’ rights. As a directly impacted person, activist, and professor, they spoke several times at the U.N. They argued that by cutting off economic, social, and cultural support, criminalization traps people in an endless cycle of isolation and dependency, fueling sex trafficking.

“Without decriminalization, we have nowhere to turn. Partners, landlords—everything is affected,” Lee said. “We want interventions before harm happens. Every single person who is living in economic precarity needs to have their survival needs met.”

The committee’s observations on sex work and trafficking were not as strong as the team would have liked, Brundige noted. However, they do express concern about the “criminalization of victims of trafficking in prostitution-related charges” and call on the U.S. to put in place measures to prevent it.

The clinic’s recommendations appear to be the first to address sex workers’ rights before the committee.

“The U.N. Human Rights Committee is very interested in learning from directly impacted people. And that’s not always the case in policymaking fora,” Brundige said. “So, the fact that people who were directly impacted by these human rights violations were given an opportunity to speak was both powerful for them and a critically important part of the committee’s process.”

Speaking before the U.N. and working with civil society leaders she’s looked up to for years was a surreal experience, Gonzalez-Navarrine said: “As someone who used to be involved in politics and studied international diplomacy in undergrad, it was a pinch me moment.”