This website uses cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.

After the Russian government interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Jens David Ohlin, Vice Dean and Professor of Law, realized that social media disinformation represented a new risk to democratic deliberation. He asked himself: Did Russia’s behavior violate international law?

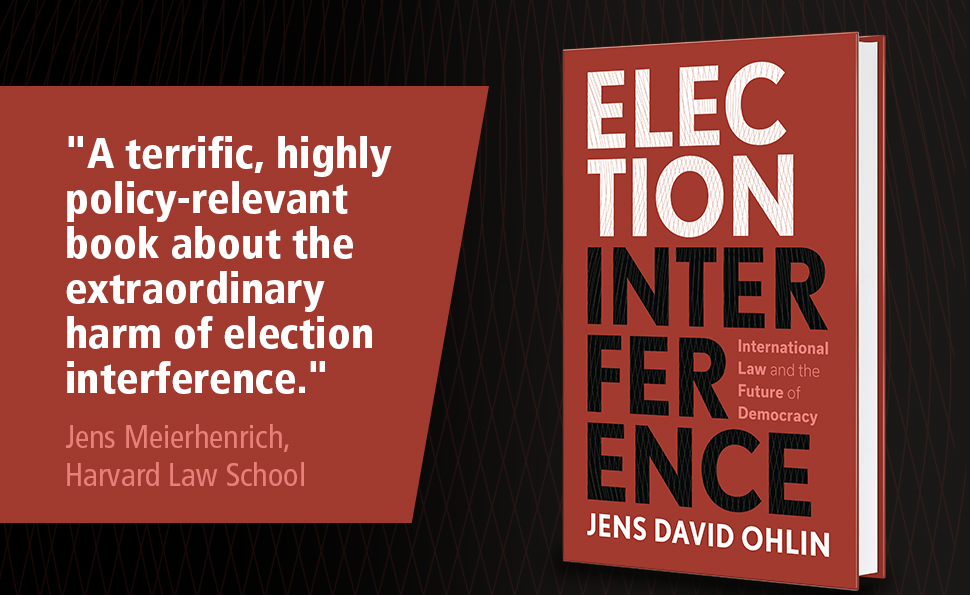

Four years later, Ohlin’s book, Election Interference: International Law and the Future of Democracy(Cambridge University Press, 2020) was published, making the case that Russia’s election meddling was illegal because it violated the collective right of self-determination.

“The definition of self-determination is that a people have the right to select their own destiny, and in a democratic system, that process is played out through the democratic institution of elections,” Ohlin said at a book celebration held on October 19. “When a foreign country ends up meddling in an election, it violates this core notion of self-determination.”

During the virtual event, moderated by Professor Odette Lienau, two experts in the field of international law praised the book for providing insights into the legal implications of Russia’s interference in the 2016 election.

Yet Duncan Hollis, Laura H. Carnell Professor of Law at Temple Law School, questioned whether the problem of foreign election interference should continue to be prioritized, given the emergence of domestic groups that are spreading misinformation on social media in the current election.

“Is the problem really the foreign origins of information or is it really how quickly misinformation and disinformation are getting amplified today?” Hollis asked. “We’re seeing a host of domestic dirty tricks — misinformation about everything from masks to the craziness of QAnon — all suggesting a broader national crisis in political deliberation.”

Ohlin acknowledged that the misinformation disseminated by domestic groups has become an increasing problem, especially since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic last spring. Yet he argued that misinformation by domestic groups is a separate problem that will be difficult to address given the constraints of the First Amendment.

Chimène Keitner, Alfred and Hanna Fromm Professor of International Law at the University of California Hastings College of the Law, commended the book for foregrounding the choice of political destiny as the ultimate value to protect.

Ohlin recommends several strategies in the book to counteract election interference, including social media firms labeling posts that come from foreign troll farms, Congress creating a new federal agency with the authority to protect elections from foreign interference, and a new federal statute criminalizing the solicitation of foreign interference.

“Unfortunately, election interference is likely to be a permanent fixture of modern democracy, especially in our social media age,” Ohlin said. “But there are concrete actions that states can take to protect their right to self-determination.”