This website uses cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.

Early in the spring 2023 semester, first-year law students in Cornell Law’s 1L Immigration Law and Advocacy Clinic are focused on learning legal theory and studying case law. They learn from legal experts in human rights, civil liberties, immigration, and advocacy. They meet with clients from the local community and integrate intercultural awareness into these interviews. But nothing quite prepares them for what they experienced in person on spring break. That’s when they traveled to rural Louisiana to meet directly with immigrants in detention centers, and to put into practice all they had learned.

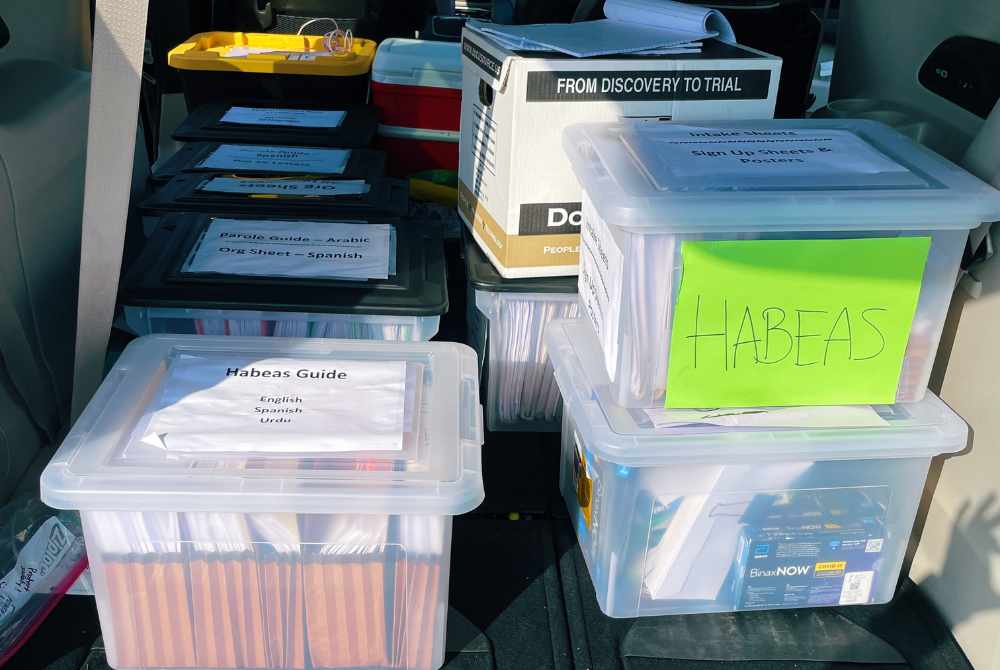

Through a partnership with the Southeast Immigrant Freedom Initiative of the Southern Poverty Law Center, the students visited two detention centers and provided assistance to 800 detained people in four days.

“Every student brought their best skills to bear,” says Jakki Kelley-Widmer, clinic director. “But they quickly saw that the cases they studied are just a legal construct of people’s lives. What these folks are really living isn’t easily addressed by the law. When students go into these facilities and actually talk with people who are detained, it is totally eye-opening and almost indescribable. It can be overwhelming.”

Arina Gorokhovska ’25 said the detention centers felt more like prisons, with “a lack of proper medical care, food, and sleep, interference with legal aid by the officers, lack of language access provided to the detainees, crooked lawyers, physical and mental abuse of the detainees, and general dehumanization.” Herself an immigrant from Ukraine, Gorokhovska said it was staggering to talk “to people who are imprisoned just for wanting a better life.”

Still, the students and their teachers were inspired by the extraordinary resilience and determination of the detained immigrants. “Most of these detained people have dire situations in their home countries,” says Kelley-Widmer, who has worked in immigration law since her own first semester in law school. “Getting to work with them is a privilege. We are lawyers and our role is to empower them with knowledge and walk beside them with compassion. This work is powerfully motivating for me.” It’s a passion she shares with her students, helping them work through the shock that many of them experience during their hands-on work with detainees.

In debriefing sessions following the spring break trip, Kelley-Widmer says she encourages the students to share their observations and their feelings in an exercise she calls “the thorn, the bud, and the rose.” For Kelley-Widmer, the biggest “rose” was “seeing the students marshal the skills they had gathered over three months and use them to effectively counsel clients, to deliver information and do meaningful advocacy.”

Similarly, Gorokhovska balanced a sense of helplessness in the face of a massive system (“like saving a grain of sand from a beach”) with inspiration that came from just doing the work. “My bud is seeing that there are people who are dedicating their lives to this cause and knowing that all of the students on this trip, including myself, learned so much and would be better lawyers for it. My rose was seeing how even in such terrible, inhuman conditions, people still build communities, friendships, and even love. They still joke and smile and celebrate holidays. It was very touching to see the joy on their faces from being spoken to in their own language and giving them a small hope that not everyone was looking away from them.”

Kelley-Widmer says the experience helps the students define their trajectory in law school and beyond. “It’s really important to have these experiences early on, because in the summer after their first year, they have to start focusing on the kind of law they want to practice and look for jobs.”