This website uses cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.

A. D. White

“We wish the new school success,” the Albany Law Journal noted acidly, when it learned of White’s plans, “but we do not expect it.” There were only a few law schools of any consequence in the country when Cornell’s department admitted its first students in 1887; most future lawyers (they were almost always men) clerked in law offices, and studied on the job.

Members of the Class of 1893, including Mary E. Kennedy (center) who was the first woman graduate of Cornell Law School.

A high school diploma was not a prerequisite for entry to Cornell’s new department; tuition was $75 a year for three hours of classes a day. Students were thirsty for knowledge: “We had to drive them out of the library at night, and had a hard time answering their questions the next morning,” wrote faculty member Charles Evans Hughes. (Hughes, who later served as chief justice of the Supreme Court, then as secretary of state, said he’d “enjoyed teaching most of all.”)

The school’s growth mirrored that of legal schooling in the country; the number of law students in the U.S. tripled over the next ten years. The law department’s standards rose. By 1917, admission required at least two years of university education. World War I saw a halt in the stream of graduates, but students returned after the Armistice. Legal study was made a graduate degree in 1924, and the department of law became a professional school. In 1925, the trustees voted to give the new institution a new name: Cornell Law School.

A lecture by Professor Cuthbert W Pound in Boardman Hall, original home of the Law School, circa 1900

By the end of World War II, law students who had fought overseas brought back internationally-scaled aspirations. In response, the Law School entered the arena of international legal studies in earnest. The faculty grew in strength and numbers over the next thirty years; graduates who had prospered endowed professorships, and research flourished. Classes in legal history and philosophy found places in the catalog of second- and third-year elective courses. So that students’ more practical legal training might not suffer, the Legal Aid Clinic was established to give students the opportunity to confront real legal problems in the real world; many other clinics followed.

Today, Andrew White’s dream has grown in a way he could hardly have anticipated as the Law School’s graduates achieve excellence in all facets of the legal profession throughout the United States and the world. The Albany Law Journal, thankfully, was wrong; the Law School’s success is undisputed.

Our inclusive approach dates back to our founder, A. D. White. His egalitarian outlook on education lives on in Cornell Law’s mission to train “lawyers in the best sense.” In a letter to the abolitionist Gerrit Smith in 1862, when slavery was still legal, White described his ambition to found a university that would provide instruction “afforded to all—regardless of sex or color.”

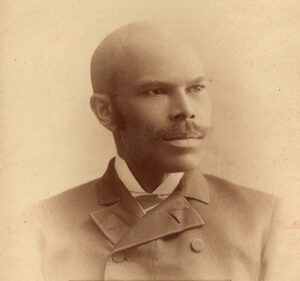

George Washington Fields, 1890

It wasn’t long before White’s vision became reality. Cornell Law’s first graduating class included George Washington Fields, the first African-American graduate of the Law School and in the first group of three black students at Cornell University. He is the only Cornell University graduate to have been born a slave. Fields would graduate in 1890 and carve a successful career as a lawyer in Hampton, Virginia.

A defining feature of the Law School is our especially rich history of producing pioneering women lawyers. Since Mary Kennedy Brown became the Law School’s first woman lawyer in 1893, there has been no shortage of notable women graduates who went on to remarkable careers, many despite, or because of, the persistent discrimination they faced. In 1919, Mary Donlon ’20, became the first woman editor-in-chief of a law review anywhere in the United States, decades before any other woman held such a title. In fact, three of the next four female editors in chief of law reviews were also from Cornell Law School as well.

Mary Donlon ’20

International students have also been part of the student body from the very beginning. Two Japanese students were part of the Law School’s first entering class in 1887.

We’re proud to continue White’s legacy to this day. We are one of the most diverse top law schools in the nation. Cornell Law’s diversity story is still being written. One of our ongoing priorities is to provide opportunities for women and minorities, both in our student body and in faculty positions. We believe the richest learning environment is one in which people from all backgrounds are encouraged to share their perspectives.